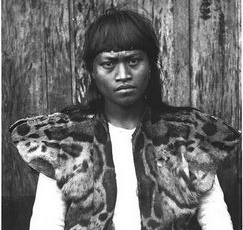

Archeological sites confirm that Formosa was populated some 12.000 years ago by Austronesian people. Today, out of Taiwan’s 23 million inhabitants around 500.000 descendant of this first settlers live in Taiwan and are trying to protect and revive their culture, language and tribal traditions.

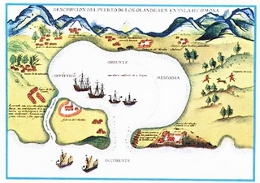

At the time of the Portuguese discovery of the island, Formosa (meaning beautiful in Portuguese), was a prime heaven for Japanese and Chinese pirates that mostly kept to the shores, and rarely dared to go inland due to the aggressive nature of the aborigine population. This situation was not to change till 1622 and 1626 when Spain and Holland, then World superpowers, decided to secure their maritime trading lines between Japan, the Philippines and Batavia and settled down in Northern and Southern Taiwan respectively. The arrival of the Europeans fueled a strong development of the local agriculture, education (the Latin alphabet tough to the aborigines by Spanish and Dutch missionaries was the first form of written language ever used in the island) and religious activity.

The Spanish presence lasted only for 20 years and was cut short by Dutch attacks on the Spanish Danshui and Keelung forts. Then between 1661 and 1662 the Dutch were in their turn expelled from the island by a sino-japanese pirate known as Koxinga, who after taking over Taiwan organized the first important migration by Chinese people to the island. The island’s colonization under Koxinga was hard and dangerous, in part due to Taiwan’s extreme geography and the aborigines’ aggressive nature, and it was not till 1885 that Imperial China decided to claim the island as part of its territory, a short lived possession it was to be, as the island was ceded to Japan in 1895 as a result of the Shimonoseki Treaty.

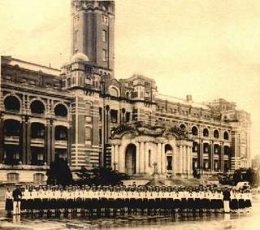

The Japanese took the task to create in Taiwan a “model colony” and while pacifying the aborigines and the different warring Chinese factions, they invested heavily in the development of key agricultural, industrial, and rail infrastructure projects. As a way to “Japanize” the locals, mandatory basic education in Japanese was introduced and it’s not infrequent to meet Taiwanese elderly people that master Japanese but have little or no command of mandarin. In a way the assimilation was so successful that native Taiwanese were quite involved in Japan’s politics and during WW II nearly 400.00 Taiwanese youth served voluntarily under the Japanese flag.

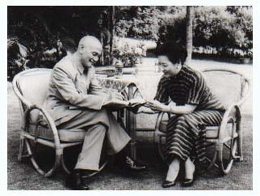

After WW II the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) ceded Taiwan’s administration to the Republic of China Kuomintang’s government. Initially Taiwanese welcomed the new government, but after a year under the government of Chiang Kai Shek’s Kuomintang party, the local population began showing signs of disaffection to the corrupt and dictatorial regime. The honeymoon coming to an end on February 28th 1947 when the government suffocated local demonstrations and started an island wide repression known as the “White Terror”.

Around 10 to 30.000 native Taiwanese are believed to have disappeared till the end of martial law, decreed by Chiang’s son Chiang Chin Kuo in 1987.Chiang Chin Kuo set the basis for a strong economic development and political reform and under his succesor Lee Teng Hui, Taiwan’s first democratic elections in 1996 were organized.

ANDRADE, Tonio (2005). How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

BORAO MATEO, José Eugenio.(2001) Spaniards in Taiwan, Nan Tien (SMC Book Co.), Vol. I (1582-1641) Taipei.

FUNG, Edmund S. K. (2000). In search of Chinese democracy: civil opposition in Nationalist China, 1929-1949. Cambridge modern China series. Cambridge University Press.

FENBY, Jonathan (2009). The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850 - 2009. Penguin Books.

DAVIDSON, James W.(1905). Island of Formosa Past and Present.